Tattoos as Souvenirs Before Mass Tourism

‘There is a strong tendency nowadays to display the American Eagle in a tattoo design actually as the whole or part of the punialo.’ Jack W. Groves, A Unique Tattoo, Apia, Sāmoa, 1952. © The Trustees of The British Museum;

When travel was rare, permanent, and written on skin

Before mass tourism, long-distance travel was exceptional. Crossing oceans or continents required time, money, and institutional access. Those who traveled far were usually sailors, soldiers, merchants, missionaries, or colonial officials. Their journeys lasted months or years and carried no guarantee of return. In that world, tattoos served as durable records of movement – fixed to the body rather than stored in luggage.

Ink functioned as proof of passage.

A Narrow Class of Travelers

Until the late 19th century, international mobility was limited to a small fraction of the population.

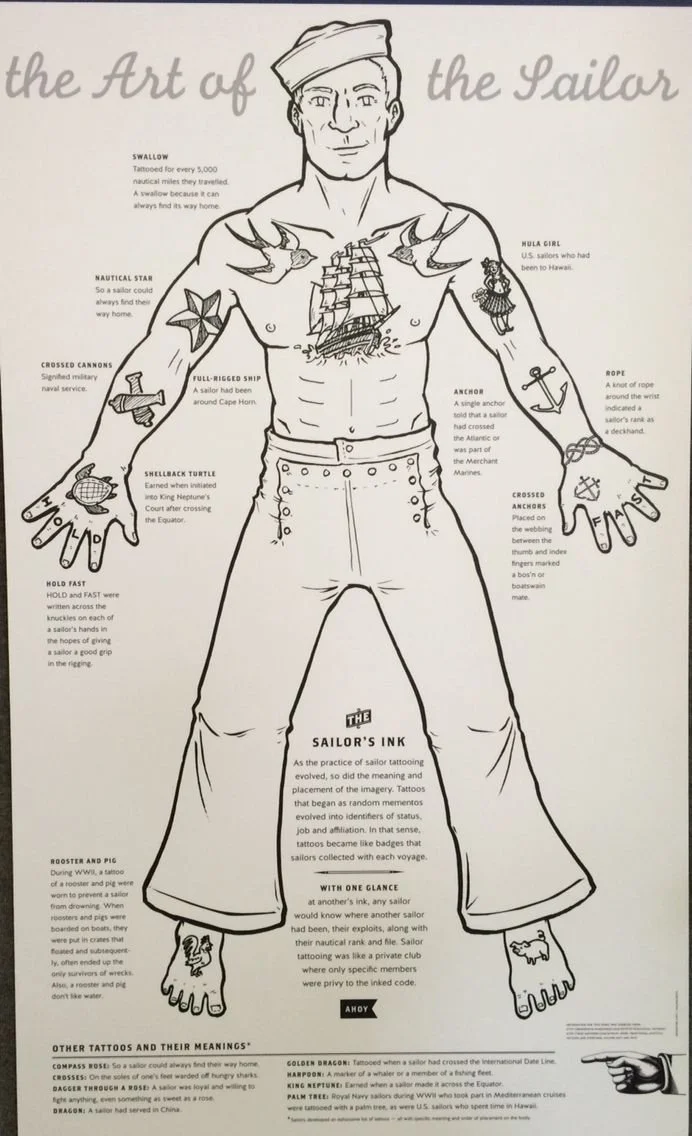

Maritime laborers were among the most mobile people of the era. Naval records and contemporary observers noted that tattooing was common aboard European and American ships by the 18th and 19th centuries. On some British vessels, tattoos were worn by a significant share of the crew. American sailors followed similar patterns.

Travel for these men was prolonged, repetitive, and often dangerous. The body became the most reliable surface on which to register experience.

Marks of Experience

Early travel-related tattoos were functional.

Common motifs included anchors, ships, swallows, religious symbols, names of vessels, dates, and occasionally references to specific crossings, such as the equator. Some designs were believed to offer protection at sea. Others served a practical purpose: identifying a sailor’s body if it was recovered without papers.

These tattoos recorded time spent away from home and survival under conditions that left little margin for sentimentality. They were not souvenirs in the modern consumer sense, but they fulfilled a similar role – anchoring memory to place.

Why Skin, Not Objects

Physical souvenirs were rare. Goods were expensive, fragile, and difficult to transport. Photography was unavailable or inaccessible. Written travel accounts circulated primarily among elites. Tattoos required no storage, crossed borders without scrutiny, and survived shipwrecks, arrests, and decades of wear.

For itinerant workers, skin offered permanence where objects could not.

Ports and Transmission

Tattooing spread through maritime networks. Sailors encountered established tattoo traditions in the Pacific, Japan, Southeast Asia, and parts of Africa. They learned techniques informally and adopted visual elements that could be reproduced quickly. Meanings were often lost or simplified in the process, while forms continued to circulate.

Ports became sites of visual exchange. Designs accumulated, overlapped, and standardized as they moved from body to body. By the time professional tattoo studios emerged in Western port cities in the late 19th century, much of their visual language had already traveled the world by sea.

Status and Discretion

Lady Randolph Churchill with her tattoo on her left arm, hidden beneath several bracelets.

Travel tattoos also carried social meaning.

Because long-distance travel was rare, a tattoo acquired abroad signaled access to distant places and prolonged absence from home. Among officers and members of the upper classes who acquired tattoos during colonial service, marks were often concealed. Their significance was private rather than performative – confirmation of experience rather than identity.

The Shift to Mass Travel

The function of tattoos changed as travel became standardized. Steamships, railways, and colonial infrastructure shortened journeys and reduced their risk. Travel became repeatable. Souvenirs became objects. Photography replaced skin as evidence of movement.

Tattooing persisted, but its role shifted from documentation to expression. What had once marked rarity became elective.

What Endures

The older logic remains visible. Modern travel tattoos still mark place, memory, and passage, even as travel itself has become routine. The difference is scale. What was once earned under conditions of uncertainty is now chosen under conditions of access.

Before postcards and passports, the body itself carried the record. Ink was the original souvenir.

If you wish to continue the tradition, visit Cacilhas Tattoo studio once in Lisbon.