Tattoos People Got to Prove They’d Been Somewhere Dangerous

War zones, rough ports, and ink earned the hard way

For much of the modern era, certain tattoos carried a specific implication: the wearer had been somewhere the safe world did not go. The proof was social – legible within communities built around risk. Sailors recognized it in one another. Soldiers read it in barracks and camps. Dockworkers saw it in port bars and boarding houses. A mark acquired far from home suggested exposure: to violence, disease, storms, coercion, the attrition of long-distance work. It was a way of making danger visible after the fact.

That logic predates mass tourism. In the centuries before cheap travel, a long voyage was not a lifestyle choice. It was labor or service. The body was one of the few surfaces that could carry evidence across borders without being lost, stolen, or confiscated.

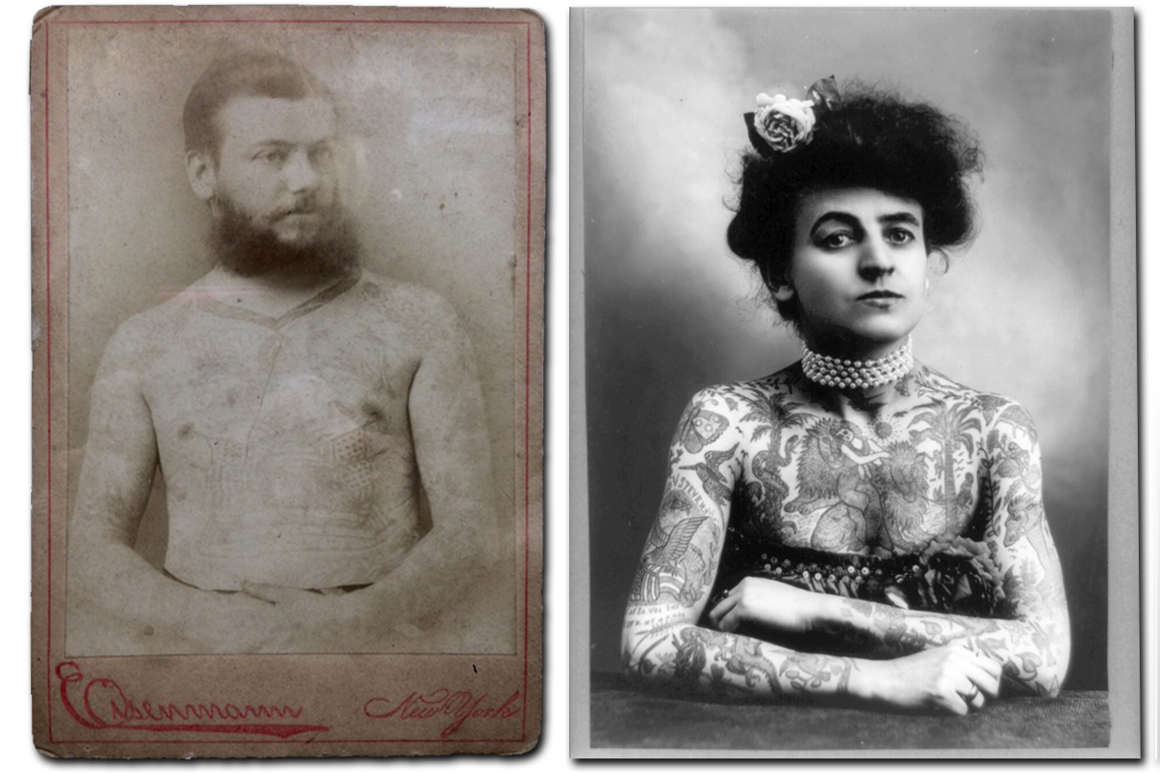

A working-class archive

Tattooing’s association with danger grew out of who traveled, and why.

By the late 18th century, tattooing had become common among sailors in the British and American worlds, with naval historians noting significant proportions of crews bearing tattoos. A major reason was simple practicality: tattoos helped identify a sailor’s body if he drowned or died without papers – a grim administrative need in an era of shipwrecks and anonymous death.

The archival trail is unusually concrete. In the United States, seamen’s “protection certificates” – documents intended to prove citizenship and reduce impressment risk – often included physical descriptions and distinguishing marks, including tattoos. Ira Dye’s study of early American seafarers, based on these applications, found tattooing common enough to be measurable across years – a statistic captured not by memoir but by bureaucracy.

The tattoo, in other words, sat at the intersection of danger and recordkeeping. It was personal, but it also entered systems of surveillance and identification.

Crossing the line

Some of the most enduring “proof” tattoos are attached to rites of passage tied to risk at sea.

One of the clearest examples is the equator-crossing tradition. Navies and merchant fleets developed elaborate line-crossing ceremonies (“shellback” rituals) to mark sailors who had crossed the equator. Folklorists have written about these ceremonies as structured initiations – the creation of status through shared ordeal.

The imagery spilled into tattoos. Naval heritage sources describe shellback-themed motifs – including turtles – as common markers of crossing the equator. A sailor could wear the event on his skin long after the voyage ended, recognizable to others who had done the same passage.

It is not necessary to romanticize this. The equator itself was not the danger. The danger was what it represented: long ocean service, months away from land, and the hazards of work done in storms, heat and disease.

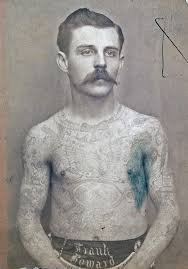

War and the fear of anonymous death

On land, tattoos served a related function in wartime: making identity durable when death was not.

During the American Civil War, soldiers tattooed names, initials, and emblems as a hedge against dying unidentified. A widely cited account, reported in later historical writing, notes the practical logic: if bodies could not be recognized, the tattoo could.

This tradition appears again and again in military contexts, though it shifts by period. Some tattoos functioned as identity and administration (names, numbers, unit symbols). Others functioned as memory and grief (names of comrades, dates, places). The body absorbed what war stripped away: continuity.

It is important to keep the claims narrow. Not all soldiers tattooed themselves. Not all military tattoos were linked to combat. But the documentary record supports the broader point: in wartime settings, tattooing took on a particular urgency because it addressed the possibility of being erased.

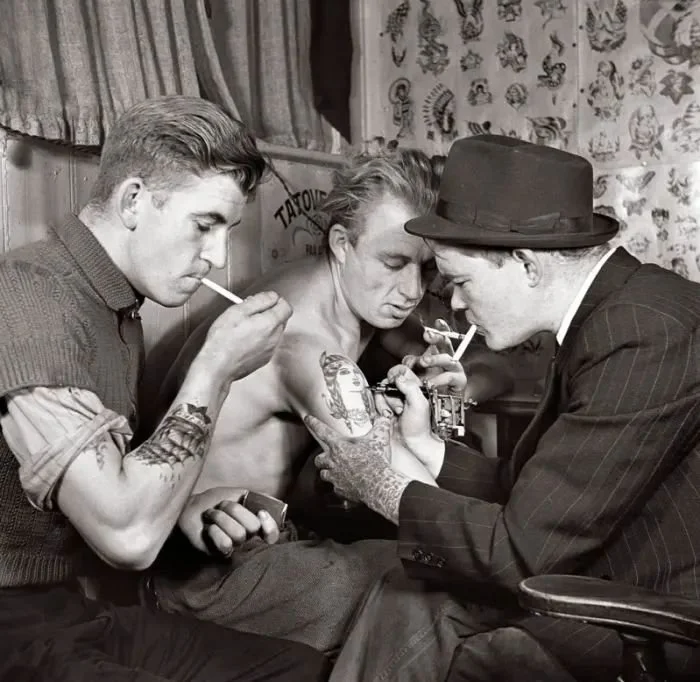

Rough ports, fast decisions

The port city is where the idea of “danger” becomes geographic.

Port towns were dense with risk: alcohol, violence, exploitative labor, disease, and the volatility of transient populations. They were also where tattooing could be purchased quickly. The sailor who lived under strict ship discipline could step ashore and spend money in minutes – on drink, sex, gambling, and ink.

This is also where tattoo styles traveled. Maritime tattooing did not spread through a single school or lineage. It spread through repetition in ports: a motif copied from a body in one city, redrawn by a different hand in the next.

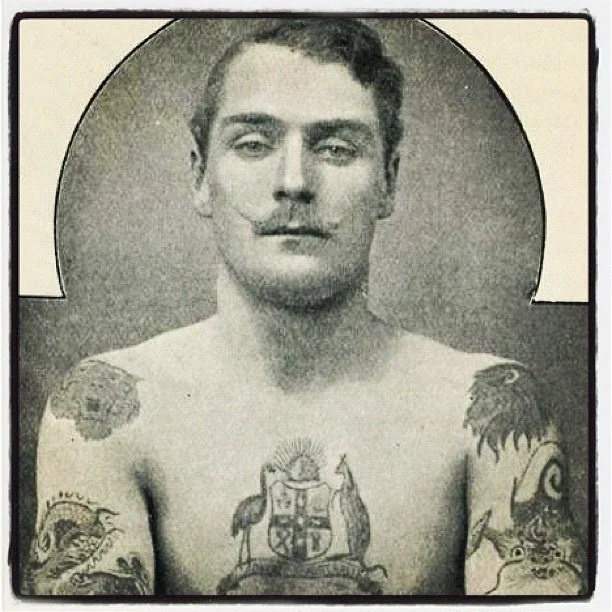

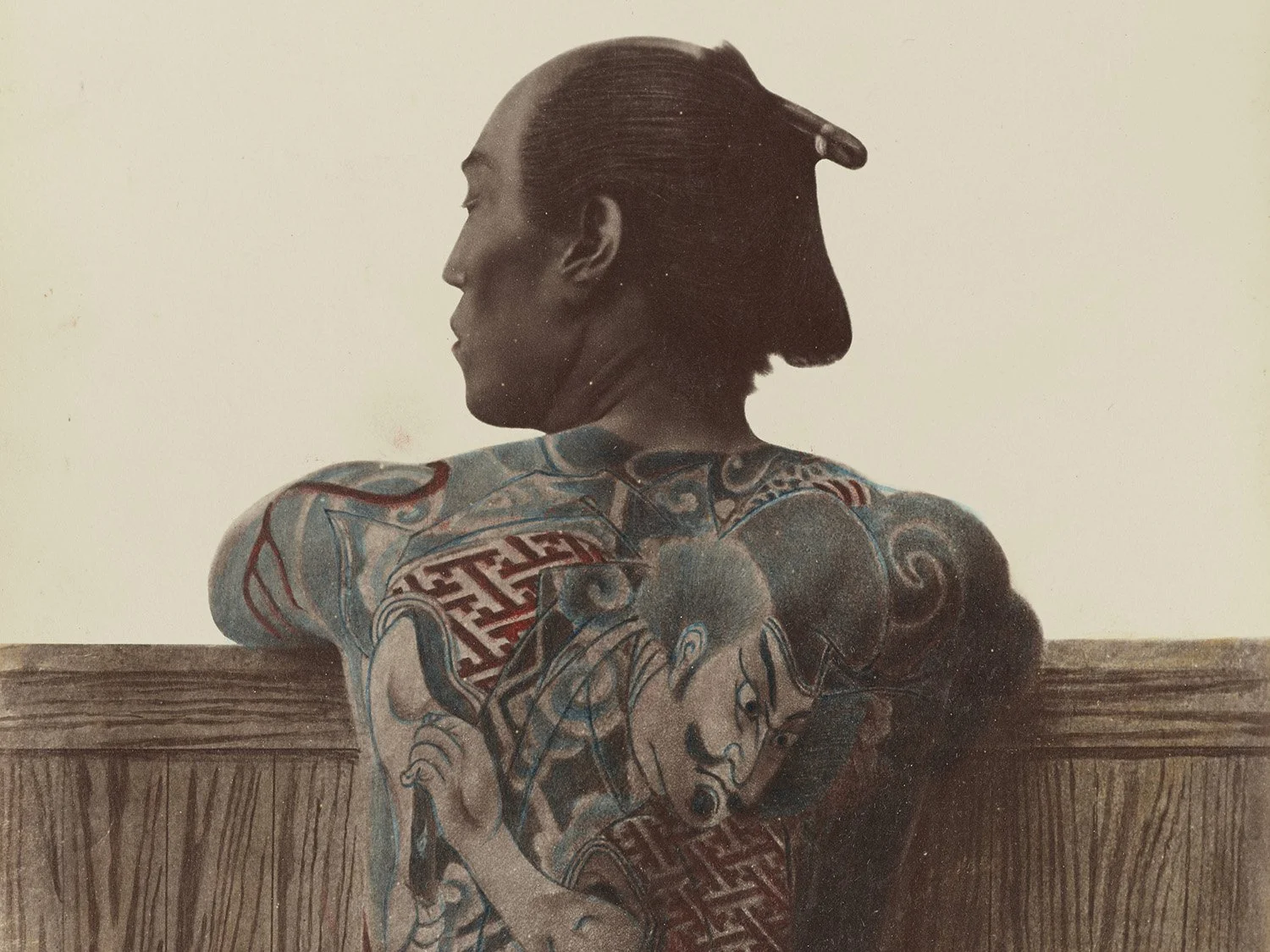

Japan in the late 19th century offers a sharp example of how “rough ports” intersected with imperial movement and aesthetic extraction. As Japan’s treaty ports opened further to foreign presence, tattooists in places like Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagasaki attracted foreign sailors and visiting elites who sought Japanese tattooing as a marker of having been there – a kind of embodied proof of access.

The Royal Collection Trust documents that teenage British princes Albert Victor and George (the future George V) were tattooed during a naval visit to Japan in 1881, receiving tattoo sessions aboard HMS Bacchante. In this world, the tattoo donly needed to exist, confirming proximity to an “edge” of the map that most people would never see.

When proof becomes a souvenir

A dangerous-place tattoo often carried two meanings at once.

Inside the group – a ship’s crew, a regiment, a port workforce – it could signal experience, endurance, and membership. Outside the group, it could signal something simpler: that the wearer had been away, had survived, had lived at higher risk than the average person.

That is the pre-tourism version of a souvenir.

As scholars of tattoo history note, motifs that carry deep cultural weight in their originating societies can be lifted into imperial circulation as portable symbols, detached from context. Maritime routes made this kind of detachment routine. A design could move farther than its language, faster than its explanations.

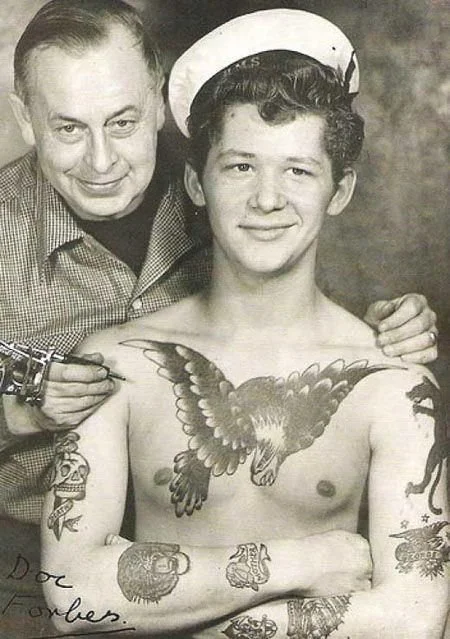

Professional tattooing and the infrastructure of danger

By the late 19th century, professional tattooing began to consolidate in major port cities.

In London, Sutherland Macdonald is widely described as the first tattooist in Britain to operate from an identifiable public premises, listed in directories by the 1890s. His clientele included people whose travel and military service gave them both the money and the motive for tattooing.

In New York, Martin Hildebrandt – a sailor and Civil War veteran – is often cited as an early professional tattooist who tattooed soldiers during the Civil War and later opened a tattoo shop in Manhattan in the 1870s. The point is not that these men “invented” tattooing, but that their careers show how a practice built in dangerous work environments moved into fixed urban businesses.

Once studios exist, danger becomes easier to purchase as an aesthetic. The risk remains real for many clients – sailors still ship out, soldiers still deploy – but the infrastructure now allows the tattoo to circulate beyond those worlds.

What survives into the present

Modern tattoo culture inherits this story, whether it acknowledges it or not.

Travel tattoos today often imitate older structures: the place name, the date, the emblem that signals “I was there.” The difference is that travel has become routine for large parts of the world, and risk has become optional. In earlier centuries, the distance itself was the hazard. The voyage was not a weekend; it was a disappearance.

That does not make contemporary tattoos inauthentic. It makes them historically different. The earlier tattoo was often a receipt for exposure. The modern tattoo is more often a memory aid or identity statement.

The older logic persists most clearly in communities where danger is still part of the job: military service, offshore work, maritime labor. Tattoos remain a way to fix a life lived in transit – to make risk legible after the fact.